The U.S. State Department has extended its territorial claims by over 1 million square kilometers, including large swaths of the Arctic and Atlantic seabeds.

Under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, countries have the right to claim any marine resources within their exclusive economic zone, which stretches 200 miles out from their coastline or halfway between two countries’ coastlines. Countries may also claim areas where the continental shelf originating within their existing boundaries extends into unclaimed areas. These claims include rights to resources on or below the seabed but not within the seas above, such as fisheries.

Under the auspices of the U.S. State Department’s Extended Continental Shelf Project, the U.S. government sought to update and define those boundaries, even though the country has not yet signed the treaty, known as UNCLOS.

While an effort to revive and pass the treaty has received renewed attention in the U.S. Senate, the State Department asserted that approval of the treaty is not necessary for its claim to be approved by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), which is the arbiter of extended continental shelf claims.

“Like other countries, the United States has rights under international law to conserve and manage the resources and vital habitats on and under its extended continental shelf,” the department said in a statement.

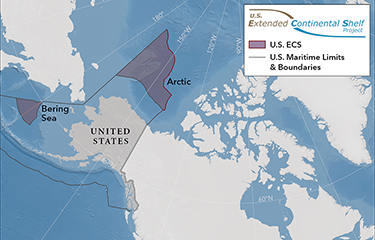

Using bathymetric and seismic data collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) data, the U.S. is claiming a total area exceeding 1 million square kilometers that spreads across seven regions.

In the Arctic, the U.S. is claiming an extended area between the U.S-Russia and U.S.-Canada maritime boundaries up to 680 miles beyond its territorial sea baseline and an additional area in the Bering Sea that stretches 340 miles out from its territorial sea baseline. In the Atlantic, the U.S. is claiming a stretch of seabed running from the U.S.-Canada maritime boundary to the U.S.-Bahamas boundary. Additional claims have been made for areas in the Pacific, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Mariana Islands region.

“The United States, like other countries, has an inherent interest in knowing – and declaring to others – the extent of its extended continental shelf and, thus, where it is entitled to exercise sovereign rights,” the State Department said. “Defining our ECS outer limits in geographical terms provides the specificity and certainty necessary to allow the United States to conserve and manage the resources of the extended continental shelf.”

James Kraska, the chair of the U.S. Naval War College’s Stockton Center for International Law, said the claim represented an important step forward in U.S. ambitions to mine more of the rare earth minerals used in a wide variety of industrial applications.

“[It] highlights American strategic interests in securing hard minerals on its seabed and subsoil,” he said. “The U.S. entitlement to sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the area is key to ensuring American economic prosperity and national security.”

The Wilson Center’s Polar Institute, which has established itself as a clearinghouse of information and perspectives related to Arctic governance and economic development, has published an extensive body of resources delving into the implications of the claim.

Polar Institute Director Rebecca Pincus, meanwhile, said the major issue with the U.S. claim is that it has not yet ratified UNCLOS.

“I think a lot of other countries around the world are going to have thoughts about how the U.S. has done this,” Pincus told Bloomberg News. "If the U.S. claim is considered by the CLCS, it might lower the chances of the U.S. Congress ratifying UNCLOS, as the delineation of the extended continental shelf claims process was a major component of what the treaty accomplished," Pincus said.

Russia recently accepted recommendations made by the CLCS regarding its own claim submission, becoming the first country to finalize the UNCLOS process for claiming extended continental shelf areas. Denmark and Canada are awaiting rulings from the commission.

Image courtesy of U.S. Extended Continental Shelf Project